Artificial Intelligence (AI)

artificial intelligence the ability of a digital computer or computer-controlled robot to perform tasks commonly associated with intelligent beings. The term is frequently applied to the project of developing systems endowed with the intellectual processes characteristic of humans, such as the ability to reason, discover meaning, generalize, or learn from past experience. Since their development in the 1940s, digital computers have been programmed to carry out very complex tasks—such as discovering proofs for mathematical theorems or playing chess—with great proficiency.

Despite continuing advances in computer processing speed and memory capacity, there are as yet no programs that can match full human flexibility over wider domains or in tasks requiring much everyday knowledge. On the other hand, some programs have attained the performance levels of human experts and professionals in executing certain specific tasks, so that artificial intelligence in this limited sense is found in applications as diverse as medical diagnosis, computer search engines, voice or handwriting recognition, and chatbots.

What is intelligence?

All but the simplest human behavior is ascribed to intelligence, while even the most complicated insect behavior is usually not taken as an indication of intelligence. What is the difference? Consider the behavior of the digger wasp, Sphex ichneumoneus. When the female wasp returns to her burrow with food, she first deposits it on the threshold, checks for intruders inside her burrow, and only then, if the coast is clear, carries her food inside.

The real nature of the wasp’s instinctual behavior is revealed if the food is moved a few inches away from the entrance to her burrow while she is inside: on emerging, she will repeat the whole procedure as often as the food is displaced. Intelligence—conspicuously absent in the case of the wasp—must include the ability to adapt to new circumstances.

Psychologists generally characterize human intelligence not by just one trait but by the combination of many diverse abilities. Research in AI has focused chiefly on the following components of intelligence: learning, reasoning, problem solving, perception, and using language.

Learning

There are a number of different forms of learning as applied to artificial intelligence. The simplest is learning by trial and error. For example, a simple computer program for solving mate-in-one chess problems might try moves at random until mate is found. The program might then store the solution with the position so that, the next time the computer encountered the same position, it would recall the solution. This simple memorizing of individual items and procedures—known as rote learning—is relatively easy to implement on a computer.

More challenging is the problem of implementing what is called generalization. Generalization involves applying past experience to analogous new situations. For example, a program that learns the past tense of regular English verbs by rote will not be able to produce the past tense of a word such as jump unless the program was previously presented with jumped, whereas a program that is able to generalize can learn the “add -ed” rule for regular verbs ending in a consonant and so form the past tense of jump on the basis of experience with similar verbs.

Reasoning

To reason is to draw inferences appropriate to the situation. Inferences are classified as either deductive or inductive. An example of the former is, “Fred must be in either the museum or the café. He is not in the café; therefore, he is in the museum,” and of the latter is, “Previous accidents of this sort were caused by instrument failure. This accident is of the same sort; therefore, it was likely caused by instrument failure.”

The most significant difference between these forms of reasoning is that in the deductive case, the truth of the premises guarantees the truth of the conclusion, whereas in the inductive case, the truth of the premises lends support to the conclusion without giving absolute assurance. Inductive reasoning is common in science, where data are collected and tentative models are developed to describe and predict future behavior—until the appearance of anomalous data forces the model to be revised.

Deductive reasoning is common in mathematics and logic, where elaborate structures of irrefutable theorems are built up from a small set of basic axioms and rules.

There has been considerable success in programming computers to draw inferences. However, true reasoning involves more than just drawing inferences: it involves drawing inferences relevant to the solution of the particular problem. This is one of the hardest problems confronting AI.

Problem solving

Problem solving, particularly in artificial intelligence, may be characterized as a systematic search through a range of possible actions in order to reach some predefined goal or solution. Problem-solving methods divide into special purpose and general purpose. A special-purpose method is tailor-made for a particular problem and often exploits very specific

Features of the situation in which the problem is embedded. In contrast, a general-purpose method is applicable to a wide variety of problems. One general-purpose technique used in AI is means-end analysis—a step-by-step, or incremental, reduction of the difference between the current state and the final goal. The program selects actions from a list of means—in the case of a simple robot, this might consist of PICKUP, PUTDOWN, MOVEFORWARD, MOVEBACK, MOVELEFT, and MOVERIGHT—until the goal is reached.

Many diverse problems have been solved by artificial intelligence programs. Some examples are finding the winning move (or sequence of moves) in a board game, devising mathematical proofs, and manipulating “virtual objects” in a computer-generated world.

Perception

A language is a system of signs having meaning by convention. In this sense, language need not be confined to the spoken word. Traffic signs, for example, form a mini-language, it being a matter of convention that means “hazard ahead” in some countries. It is distinctive of languages that linguistic units possess meaning by convention, and linguistic meaning is very different from what is called natural meaning, exemplified in statements such as “Those clouds mean rain” and “The fall in pressure means the valve is malfunctioning.”

An important characteristic of full-fledged human languages—in contrast to birdcalls and traffic signs—is their productivity. A productive language can formulate an unlimited variety of sentences.

Large language models like ChatGPT can respond fluently in a human language to questions and statements. Although such models do not actually understand language as humans do but merely select words that are more probable than others, they have reached the point where their command of a language is indistinguishable from that of a normal human. What, then, is involved in genuine understanding, if even a computer that uses language like a native human speaker is not acknowledged to understand? There is no universally agreed upon answer to this difficult question.

Methods and Goals in AI

Symbolic vs. connectionist approaches

AI research follows two distinct, and to some extent competing, methods, the symbolic (or “top-down”) approach, and the connectionist (or “bottom-up”) approach. The top-down approach seeks to replicate intelligence by analyzing cognition independent of the biological structure of the brain, in terms of the processing of symbols—whence the symbolic label. The bottom-up approach, on the other hand, involves creating artificial neural networks in imitation of the brain’s structure—whence the connectionist label.

To illustrate the difference between these approaches, consider the task of building a system, equipped with an optical scanner, that recognizes the letters of the alphabet. A bottom-up approach typically involves training an artificial neural network by presenting letters to it one by one, gradually improving performance by “tuning” the network. (Tuning adjusts the responsiveness of different neural pathways to different stimuli.)

In contrast, a top-down approach typically involves writing a computer program that compares each letter with geometric descriptions. Simply put, neural activities are the basis of the bottom-up approach, while symbolic descriptions are the basis of the top-down approach.

In The Fundamentals of Learning (1932), Edward Thorndike, a psychologist at Columbia University, New York City, first suggested that human learning consists of some unknown property of connections between neurons in the brain.

In The Organization of Behavior (1949), Donald Hebb, a psychologist at McGill University, Montreal, suggested that learning specifically involves strengthening certain patterns of neural activity by increasing the probability (weight) of induced neuron firing between the associated connections.

In 1957 two vigorous advocates of symbolic AI—Allen Newell, a researcher at the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California, and Herbert Simon, a psychologist and computer scientist at Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh—summed up the top-down approach in what they called the physical symbol system hypothesis.

This hypothesis states that processing structures of symbols is sufficient, in principle, to produce artificial intelligence in a digital computer and that, moreover, human intelligence is the result of the same type of symbolic manipulations.

During the 1950s and ’60s the top-down and bottom-up approaches were pursued simultaneously, and both achieved noteworthy, if limited, results. During the 1970s, however, bottom-up AI was neglected, and it was not until the 1980s that this approach again became prominent. Nowadays both approaches are followed, and both are acknowledged as facing difficulties.

Symbolic techniques work in simplified realms but typically break down when confronted with the real world; meanwhile, bottom-up researchers have been unable to replicate the nervous systems of even the simplest living things. Caenorhabditis elegans, a much-studied worm, has approximately 300 neurons whose pattern of interconnections is perfectly known. Yet connectionist models have failed to mimic even this worm. Evidently, the neurons of connectionist theory are gross oversimplifications of the real thing.

Artificial general intelligence (AGI), applied AI, and cognitive simulation

Employing the methods outlined above, AI research attempts to reach one of three goals: artificial general intelligence (AGI), applied AI, or cognitive simulation. AGI (also called strong AI) aims to build machines that think. The ultimate ambition of AGI is to produce a machine whose overall intellectual ability is indistinguishable from that of a human being’s. To date, progress has been uneven.

Despite advances in large-language models, it is debatable whether AGI can emerge from even more powerful models or if a completely different approach is needed. Indeed, some researchers working in AI’s other two branches view AGI as not worth pursuing.

Applied AI, also known as advanced information processing, aims to produce commercially viable “smart” systems—for example, “expert” medical diagnosis systems and stock-trading systems. Applied AI has enjoyed considerable success.

In cognitive simulation, computers are used to test theories about how the human mind works—for example, theories about how people recognize faces or recall memories. Cognitive simulation is already a powerful tool in both neuroscience and cognitive psychology.

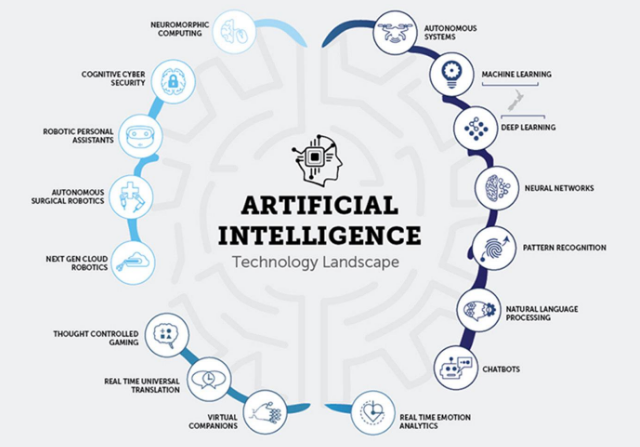

AI technology

In the early 21st century faster processing power and larger datasets (“big data”) brought artificial intelligence out of computer science departments and into the wider world. Moore’s law, the observation that computing power doubled roughly every 18 months, continued to hold true. The stock responses of the early chatbot Eliza fit comfortably within 50 kilobytes; the language model at the heart of ChatGPT was trained on 45 terabytes of text.

Machine learning

The ability of neural networks to take on added layers and thus work on more-complex problems increased in 2006 with the invention of the “greedy layer-wise pretraining” technique, in which it was found that it was easier to train each layer of a neural network individually than to train the whole network from input to output.

This improvement in neural network training led to a type of machine learning called “deep learning,” in which neural networks have four or more layers, including the initial input and the final output. Moreover, such networks are able to learn unsupervised—that is, to discover features in data without initial prompting.

Among the achievements of deep learning have been advances in image classification in which specialized neural networks called convolution neural networks (CNNs) are trained on features found in a set of images of many different types of objects.

The CNN is then able to take an input image, compare it with features in images in its training set, and classify the image as being of, for example, a cat or an apple. One such network, PReLU-net by Kaiming He and collaborators at Microsoft Research, has classified images even better than a human did.

The achievement of Deep Blue in beating world chess champion Garry Kasparov was surpassed by DeepMind’s AlphaGo, which mastered go, a much more complicated game than chess. AlphaGo’s neural networks learned to play go from human players and by playing itself. It defeated top go player Lee Sedol 4–1 in 2016.

AlphaGo was in turn surpassed by AlphaGo Zero, which, starting from only the rules of go, was eventually able to defeat AlphaGo 100–0. A more general neural network, Alpha Zero, was able to use the same techniques to quickly master chess and shogi.

Machine learning has found applications in many fields beyond gaming and image classification. The pharmaceutical company Pfizer used the technique to quickly search millions of possible compounds in developing the COVID-19 treatment Paxlovid.

Google uses machine learning to filter out spam from the inbox of Gmail users. Banks and credit card companies use historical data to train models to detect fraudulent transactions.

Deepfakes are AI-generated media produced using two different deep-learning algorithms: one that creates the best possible replica of a real image or video and another that detects whether the replica is fake and, if it is, reports on the differences between it and the original.

The first algorithm produces a synthetic image and receives feedback on it from the second algorithm; it then adjusts it to make it appear more real. The process is repeated until the second algorithm does not detect any false imagery.

Deepfake media portray images that do not exist in reality or events that have never occurred. Widely circulated deepfakes include an image of Pope Francis in a puffer jacket, an image of former U.S. president Donald Trump in a scuffle with police officers, and a video of Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg giving a speech about his company’s nefarious power. Such events did not occur in real life.

Large language models and natural language processing

Natural language processing (NLP) involves analyzing how computers can process and parse language similarly to the way humans do. To do this, NLP models must use computational linguistics, statistics, machine learning, and deep-learning models. Early

NLP models were hand-coded and rule-based but did not account for exceptions and nuances in language. Statistical NLP was the next step, using probability to assign the likelihood of certain meanings to different parts of text. Modern NLP systems use deep-learning models and techniques that help them to “learn” as they process information.

Prominent examples of modern NLP are language models that use AI and statistics to predict the final form of a sentence on the basis of existing portions. In large language model (LLM), the word large refers to the parameters, or variables and weights, used by the model to influence the prediction outcome.

Although there is no definition for how many parameters are needed, LLM training datasets range in size from 110 million parameters (Google’s BERTbase model) to 340 billion parameters (Google’s PaLM 2 model). Large also refers to the sheer amount of data used to train an LLM, which can be multiple petabytes in size and contain trillions of tokens, which are the basic units of text or code, usually a few characters long, that are processed by the model.

One popular language model was GPT-3, released by OpenAI in June 2020. One of the first LLMs, GPT-3 could solve high-school-level math problems as well as create computer programs. GPT-3 was the foundation of ChatGPT software, released in November 2022. ChatGPT almost immediately disturbed academics, journalists, and others because of concern that it was impossible to distinguish human writing from ChatGPT-generated writing.

A flurry of LLMs and chatbots based on them followed in ChatGPT’s wake. Microsoft added the chatbot Copilot in 2023 to its Windows 11 operating system, its Bing search engine, and its Edge browser. That same year, Google released a chatbot, Bard (later Gemini), and in 2024, the company announced that “AI Overviews” of subjects would appear at the top of search results.

One issue with LLMs is “hallucinations”: rather than communicating to a user that it does not know something, the model responds with probable but inaccurate text based on the user’s prompts. This issue may be partially attributed to using LLMs as search engines rather than in their intended role as text generators.

One method to combat hallucinations is known as prompt engineering, whereby engineers design prompts that aim to extract the optimal output from the model. For example, one such prompt style is chain-of-thought, in which the initial prompt contains both an example question and a carefully worked out answer to show the LLM how to proceed.

Other examples of machines using NLP are voice-operated GPS systems, customer service chatbots, and language translation programs. In addition, businesses use NLP to enhance understanding of and service to consumers by auto-completing search queries and monitoring social media.

Programs such as OpenAI’s DALL-E, Stable Diffusion, and Midjourney use NLP to create images based on textual prompts, which can be as simple as “a red block on top of a green block” or as complex as “a cube with the texture of a porcupine.” The programs are trained on large datasets with millions or billions of text-image pairs—that is, images with textual descriptions.

NLP presents certain issues, especially as machine-learning algorithms and the like often express biases implicit in the content on which they are trained. For example, when asked to describe a doctor, language models may be more likely to respond with “He is a doctor” than “She is a doctor,” demonstrating inherent gender bias.

Bias in NLP can have real-world consequences. For instance, in 2015 Amazon’s NLP program for résumé screening to aid in the selection of job candidates was found to discriminate against women, as women were underrepresented in the original training set collected from employees.

Autonomous vehicles

Machine learning and AI are foundational elements of autonomous vehicle systems. Vehicles are trained on complex data (e.g., the movement of other vehicles, road signs) with machine learning, which helps to improve the algorithms they operate under. AI enables vehicles’ systems to make decisions without needing specific instructions for each potential situation.

In order to make autonomous vehicles safe and effective, artificial simulations are created to test their capabilities. To create such simulations, black-box testing is used, in contrast to white-box validation. White-box testing, in which the internal structure of the system being tested is known to the tester, can prove the absence of failure.

Black-box methods are much more complicated and involve taking a more adversarial approach. In such methods, the internal design of the system is unknown to the tester, who instead targets the external design and structure. These methods attempt to find weaknesses in the system to ensure that it meets high safety standards.

As of 2024, fully autonomous vehicles are not available for consumer purchase. Certain obstacles have proved challenging to overcome. For example, maps of almost four million miles of public roads in the United States would be needed for an autonomous vehicle to operate effectively, which presents a daunting task for manufacturers.

Additionally, the most popular cars with a “self-driving” feature, those of Tesla, have raised safety concerns, as such vehicles have even headed toward oncoming traffic and metal posts. AI has not progressed to the point where cars can engage in complex interactions with other drivers or with cyclists or pedestrians. Such “common sense” is necessary to prevent accidents and create a safe environment.

In October 2015 Google’s self-driving car, Waymo (which the company had been working on since 2009) completed its first fully driverless trip with one passenger. The technology had been tested on one billion miles within simulations, and two million miles on real roads. Waymo, which boasts a fleet of fully electric-powered vehicles, operates in San Francisco and Phoenix, where users can call for a ride, much as with Uber or Lyft.

The steering wheel, gas pedal, and brake pedal operate without human guidance, differentiating the technology from Tesla’s autonomous driving feature. Though the technology’s valuation peaked at $175 billion in November 2019, it had sunk to just $30 billion by 2020. Waymo is being investigated by the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) after more than 20 different reports of traffic violations. In certain cases, the vehicles drove on the wrong side of the road and in one instance, hit a cyclist.

Virtual assistants

Virtual assistants (VAs) serve a variety of functions, including helping users schedule tasks, making and receiving calls, and guiding users on the road. These devices require large amounts of data and learn from user input to become more effective at predicting user needs and behavior.

The most popular VAs on the market are Amazon Alexa, Google Assistant, and Apple’s Siri. Virtual assistants differ from chatbots and conversational agents in that they are more personalized, adapting to an individual user’s behavior and learning from it to improve over time.

Human-machine communication began in the 1960s with Eliza. PARRY, designed by the psychiatrist Kenneth Colby, followed in the early 1970s and was designed to mimic a conversation with a person with paranoid schizophrenia. Simon, designed by IBM in 1994, was one of the first devices that could technically be called a “smartphone,” and was marketed as a personal digital assistant (PDA).

Simon was the first device to feature a touchscreen, and it had email and fax capability as well. Although Simon was not technically a VA, its development was essential in creating future assistants. In February 2010 Siri, the first modern VA, was introduced for iOS, Apple’s mobile operating system, with the iPhone 4S. Siri was the first VA able to be downloaded to a smartphone.

Voice assistants parse human speech by breaking it down into distinct sounds known as phonemes, using an automatic speech recognition (ASR) system. After breaking down the speech, the VA analyzes and “remembers” the tone and other aspects of the voice to recognize the user. Over time, VAs have become more sophisticated through machine learning, as they have access to many millions of words and phrases. In addition, they often use the Internet to find answers to user questions—for example, when a user asks for a weather forecast.

Risks

AI poses certain risks in terms of ethical and socioeconomic consequences. As more tasks become automated, especially in such industries as marketing and health care, many workers are poised to lose their jobs. Although AI may create some new jobs, these may require more technical skills than the jobs AI has replaced.

Moreover, AI has certain biases that are difficult to overcome without proper training. For example, U.S. police departments have begun using predictive policing algorithms to indicate where crimes are most likely to occur. However, such systems are based partly on arrest rates,

which are already disproportionately high in Black communities. This may lead to over-policing in such areas, which further affects these algorithms. As humans are inherently biased, algorithms are bound to reflect human biases.

Privacy is another aspect of AI that concerns experts. As AI often involves collecting and processing large amounts of data, there is the risk that this data will be accessed by the wrong people or organizations. With generative AI, it is even possible to manipulate images and create fake profiles. AI can also be used to survey populations and track individuals in public spaces.

Experts have implored policymakers to develop practices and policies that maximize the benefits of AI while minimizing the potential risks. In January 2024 singer Taylor Swift was the target of sexually explicit non-consensual deepfakes that were widely circulated on social media. Many individuals had already faced this type of online abuse (made possible by AI), but Swift’s status brought the issue to the forefront of public policy.

LLMs are located at data centers that require large amounts of electricity. In 2020 Microsoft pledged that it would be carbon neutral by 2030. In 2024 it announced that in the previous fiscal year its carbon emissions had increased by almost 30 percent, mostly from the building materials and hardware required in building more data centers.

A ChatGPT query requires about 10 times more electricity than a Google Search. Goldman Sachs has estimated that data centers will use about 8 percent of U.S. electricity in 2030.

As of 2024 there are few laws regulating AI. Existing laws such as the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) do govern AI models but only insofar as they use personal information. The most wide-reaching regulation is the EU’s AI Act,

which passed in March 2024. Under the AI Act, models that perform social scoring of citizens’ behavior and characteristics and that attempt to manipulate users’ behavior are banned. AI models that deal with “high-risk” subjects, such as law enforcement and infrastructure, must be registered in an EU database.

AI has also led to issues concerning copyright law and policy. In 2023 the U.S. government Copyright Office began an initiative to investigate the issue of AI using copyrighted works to generate content. That year almost 15 new cases of copyright-related suits were filed against companies involved in creating generative AI programs.

One prominent company, Stability AI, came under fire for using unlicensed images to generate new content. Getty Images, which filed the suit, added its own AI feature to its platform, partially in response to the host of services that offer “stolen imagery.” There are also questions of whether work created by AI is worthy of a copyright label. Currently, AI-made content cannot be copyrighted, but there are arguments for and against copyrighting it.

Although many AI companies claim that their content does not require human labor, in many cases, such “groundbreaking” technology is reliant on exploited workers from developing countries. For example, a Time magazine investigation found that OpenAI had used Kenyan workers (who had been paid less than $2 an hour) to sort through text snippets in order to help remove toxic and sexually explicit language from ChatGPT.

The project was canceled in February 2022 because of how traumatic the task was for workers. Although Amazon had marketed its Amazon Go cashier-less stores as being fully automated (e.g., its AI could detect the items in a customer’s basket), it was revealed that the “Just Walk Out” technology was actually powered by outsourced labor from India, where more than a thousand workers operated as “remote cashiers,” leading to the joke that, in this case, AI stood for Actually Indians.

Is artificial general intelligence (AGI) possible?

Artificial general intelligence (AGI), or strong AI—that is, artificial intelligence that aims to duplicate human intellectual abilities—remains controversial and out of reach. The difficulty of scaling up AI’s modest achievements cannot be overstated.

However, this lack of progress may simply be testimony to the difficulty of AGI, not to its impossibility. Let us turn to the very idea of AGI. Can a computer possibly think? The theoretical linguist Noam Chomsky suggests that debating this question is pointless, for it is an essentially arbitrary decision whether to extend common usage of the word think to include machines.

There is, Chomsky claims, no factual question as to whether any such decision is right or wrong—just as there is no question as to whether our decision to say that airplanes fly is right, or our decision not to say that ships swim is wrong. However, this seems to oversimplify matters. The important question is, Could it ever be appropriate to say that computers think and, if so, what conditions must a computer satisfy in order to be so described?

Some authors offer the Turing test as a definition of intelligence. However, the mathematician and logician Alan Turing himself pointed out that a computer that ought to be described as intelligent might nevertheless fail his test if it were incapable of successfully imitating a human being. For example, ChatGPT often invokes its status as a large language model and thus would be unlikely to pass the Turing test.

If an intelligent entity can fail the test, then the test cannot function as a definition of intelligence. It is even questionable whether passing the test would actually show that a computer is intelligent, as the information theorist Claude Shannon and the AI pioneer John McCarthy pointed out in 1956. Shannon and McCarthy argued that, in principle, it is possible to design a machine containing a complete set of canned responses to all the questions that an interrogator could possibly ask during the fixed time span of the test.

Like PARRY, this machine would produce answers to the interviewer’s questions by looking up appropriate responses in a giant table. This objection seems to show that, in principle, a system with no intelligence at all could pass the Turing test.

In fact, AI has no real definition of intelligence to offer, not even in the subhuman case. Rats are intelligent, but what exactly must an artificial intelligence achieve before researchers can claim that it has reached rats’ level of success? In the absence of a reasonably precise criterion for when an artificial system counts as intelligent, there is no objective way of telling whether an AI research program has succeeded or failed.

One result of AI’s failure to produce a satisfactory criterion of intelligence is that, whenever researchers achieve one of AI’s goals—for example, a program that can hold a conversation like GPT or beat the world chess champion like Deep Blue—critics are able to say, “

That’s not intelligence!” Marvin Minsky’s response to the problem of defining intelligence is to maintain—like Turing before him—that intelligence is simply our name for any problem-solving mental process that we do not yet understand. Minsky likens intelligence to the concept of “unexplored regions of Africa”: it disappears as soon as we discover it.

Artificial Intelligence:

References

1. APA (American Psychological Association) Style:

When referencing books, articles, or web pages about AI in APA, follow this format

Book

Author, A. A. (Year). Title of the book. Publisher.

Example: Russell, S., & Norvig, P. (2020). Artificial intelligence: A modern approach (4th ed.). Pearson.

Journal Article

Author, A. A., & Author, B. B. (Year). Title of the article. Title of the Periodical, volume number(issue number), pages.

Example: LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y., & Hinton, G. (2015). Deep learning. Nature, 521(7553), 436-444.

2. MLA (Modern Language Association) Style:

For MLA, the following formats can be used

Book

Author’s Last Name, First Name. Title of Book. Edition, Publisher, Year.

Example: Russell, Stuart, and Peter Norvig. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. 4th ed., Pearson, 2020.

Journal Article

Book

- Author’s Last Name, First Name, and Second Author’s First Name Last Name. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal, vol. number, no. number, Year, pages.

- Example: LeCun, Yann, Yoshua Bengio, and Geoffrey Hinton. “Deep Learning.” Nature, vol. 521, no. 7553, 2015, pp. 436-444.

3. Chicago Style:

In Chicago style, you can use the following formats:

Book

- Author Last Name, First Name. Title of Book. Edition. City: Publisher, Year.

- Example: Russell, Stuart, and Peter Norvig. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. 4th ed. New York: Pearson, 2020

Journal Article

Author Last Name, First Name. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal Volume Number, no. Issue Number (Year): Page Range. DOI or URL.

Example: LeCun, Yann, Yoshua Bengio, and Geoffrey Hinton. “Deep Learning.” Nature 521, no. 7553 (2015): 436-444.

1 thought on “Artificial Intelligence”